‘När Europeisk fotboll går mot ruinen brant, lever vi kvar i en tillvaro med Guldkant’

The message stretched across two vast banners, spanning the expanse of the Northern Stand of the Eleda Stadium. Malmo’s fans had something to say, and the visit of Rangers in September for the first game of the club’s Europa League campaign provided the perfect chance to say it. “While European football stands on the brink of ruin,” it read, “we’re living on the edge of a golden age.”

It certainly feels that way, these days, at Malmo. There was something fitting about the timing of the display: the richest, traditionally most successful team in Sweden — the only Scandinavian club ever to reach a European Cup final — not just back in European competition once again, but a few weeks away from sailing to yet another domestic championship.

The fans’ sentiment, though, was a little broader than that. The two banners framed a choreographed display celebrating not Malmo’s achievements but the model that has allowed them to take place. As the teams took to the field, the fans in the Northern Stand lifted pieces of card into the air. Taken together, they read: “51%”.

Sweden is intensely proud to be European football’s great outlier. As in Germany, the country’s clubs must — by law — be majority-owned by their fans. The teams of the top-flight Allsvenskan are not properties to be traded by private equity houses or corporate capitalists or multi-club networks or wolverine princelings. The status was hard won, and remains fiercely guarded.

If anything, though, Sweden goes further even than the German Bundesliga. Broadcasters must give at least two months’ notice if they intend to move games for live television broadcast. Teams are not asked to travel more than 30 miles for midweek fixtures. Fans have, thus far, managed to stave off the introduction of video assistant referees, on the grounds that it would spoil the experience for those inside the stadiums. It is a league designed by fans, for fans.

And it has worked. At a time when many European leagues are confronting a challenging economic future, Sweden’s is thriving. In 2012, a survey found that only 11 per cent of Swedish fans regarded the Allsvenskan as their favourite sporting competition; the Premier League, the Champions League and the country’s top division of ice hockey all fared better. A decade on, that figure had risen to 40 per cent. In the same timeframe, attendances have doubled, and revenues trebled.

In many ways, Malmo encapsulate all that is good about Sweden’s approach. The club are Swedish football’s Platonic ideal; an authentically organic success story. At the turn of the century, they were marooned in the country’s second division — 25 years later, they stand once more as their country’s pre-eminent force.

Guldet stannar i Malmö. pic.twitter.com/zhKxuIrHm4

— Malmö FF (@Malmo_FF) October 28, 2024

There has been no outside investment, no billionaire benefactor, no deus ex machina, just the long-term vision, smart decision-making and judicious thinking of a club owned and operated by the fans. “We have earned everything ourselves,” the club’s chief executive, Niclas Carlnen, says. The same view, almost word for word, was expressed by executives at Allsvenskan.

The problem — certainly for the league, and quite possibly for Malmo themselves — is the risk that the club are, in effect, run too well. That their success starts to make Sweden’s model look less like a strength and more like a weakness. That this is not the start of a golden age, but something more like the end of one.

Philipp Longo has to think for a moment before he can choose his lowest moment as a Malmo fan.

That is, he is keenly aware, because he is in a position of privilege. He has been supporting the team for 15 years, give or take. He started going to games at the Eleda Stadium when he was nine or 10, and now devotes much of his spare time to watching them on the road, too.

Throughout it all, the bad times have been thin on the ground. Eventually, he lands on the 2018 season. That year, Malmo slumped in form, fired a manager, and were forced to scramble to make a raft of mid-season signings to try to stem the damage. “It was total chaos,” Longo says.

That is as bad as he can remember. And in the end, Malmo still finished third.

Malmo scramble away a shot on goal by Hacken during a match in 2018 (Nils Petter Nilsson/Getty Images)

That season aside, Longo’s experience as a Malmo fan has largely been sunshine and rainbows.

He has seen his team make the group stage of the Champions League three times, and the Europa League five times, including in the current season. He has celebrated winning the Swedish cup twice and watched them claim so many league titles he has lost count. “This year made it either seven or eight, I think,” he says.

This is not false modesty or feigned disinterest: Longo is sincerely unsure, as illustrated by the fact that the correct answer is actually nine. “That kind of says it all,” he says. Malmo, in the past decade, have won so much that even the club’s most ardent fans have difficulty keeping track.

For Sweden, that represents a considerable sea change. One of the primary allures of the Allsvenskan, over the past two decades, has been its competitive balance. The Swedish league has developed a tendency to create thrilling, down-to-the-wire title races — four of the past seven have gone to the final day, occasionally with more than one team involved — and to produce a far richer variety of champions than any comparable league in Europe.

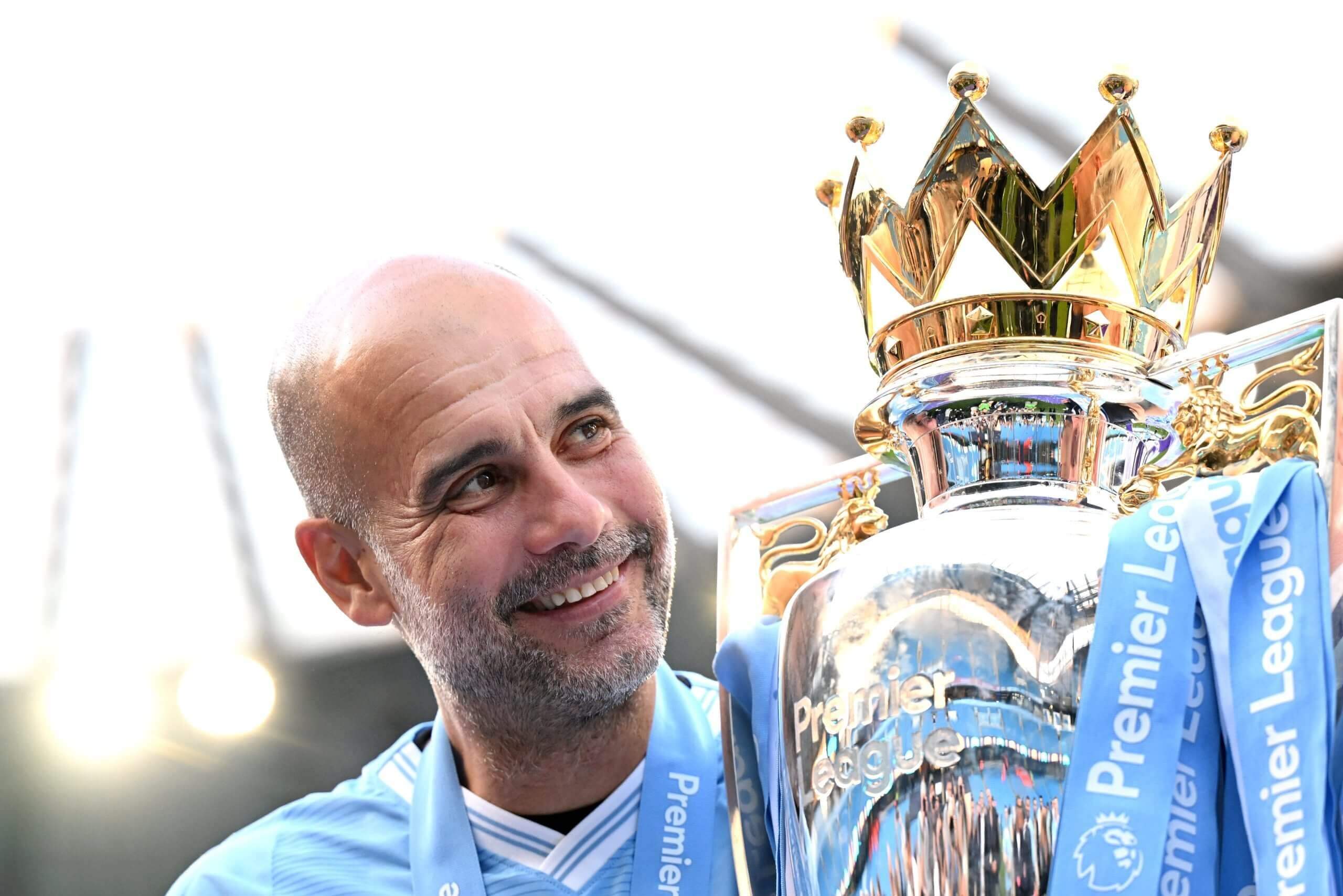

Most of the major leagues, for example, are dominated by just a handful of clubs. Six teams have won the Premier League this century. Six have won the Bundesliga in that time, too. In Italy’s Serie A, it is five, and Spain’s La Liga has had four champions.

Since 2000, only six clubs have won the Premier League. Manchester City have done it eight times, including winning six of the past seven (Michael Regan/Getty Images)

The same pattern has held in what might be termed Europe’s middleweight leagues, Sweden’s natural peers. Denmark has had five champions since 2000, Belgium six, Hungary and Norway seven. Sweden, by contrast, has produced 11, a figure that only Poland (eight) and Romania (nine) even come close to matching.

That diversity can be interpreted as both a consequence of Sweden’s model — the absence of external investment means no club have an insurmountable financial advantage over their rivals — and a driver of its success. Attendances and interest alike rise when both individual games and seasons as a whole do not feel as though their outcomes are pre-ordained.

Now, though, the landscape has shifted.

Malmo’s initial growth, according to Carlnen, can be attributed to the “risks” taken by his “visionary” predecessors. “They took the decision to build the new stadium, to take the risk to do all these things that elevate us now,” he says.

Increasingly, it is sustained by something else entirely. “In the last seven or eight years, we have a lot to thank the European competitions for,” says Longo. “I have the feeling that a lot of our success has been down to being in Europe.”

Malmo’s history, popularity and infrastructure have long meant it had a financial edge on most, or all, of its opponents; that has been compounded by the money that has flooded into their coffers from frequent appearances in the Champions League or Europa League.

A single group-stage campaign in the former can be worth around $40million (£31.8m) — not too far off the club’s ordinary annual turnover; even the $15m or so on offer in the Europa League is transformative in a league such as Sweden’s. “There is no way around it,” says Isak Eden, the head of the Swedish Football Supporters’ Union. “Malmo has a super advantage.”

It shows.

Malmo have now claimed four of the past five championships, winning the most recent edition of the Allsvenskan with several games to spare. Longo believes the club’s budget is almost double that of their closest competitors.

Daniel Andersson, Malmo’s technical director, suggests that is an exaggeration. He does not dispute, though, that the wealth gap is real, and it is growing.

Gårdagen. pic.twitter.com/J0QKD6g9Gn

— Malmö FF (@Malmo_FF) October 29, 2024

Sweden, for so long the great outlier, now appears to be caught in the same trap as so many other leagues in Europe, from Bulgaria to Belarus, Scotland to Serbia: one in which the money earned by teams getting into Europe creates a cycle that is simultaneously virtuous and vicious, in which success not only breeds success but stifles competition. The impact would likely be significantly greater if, or when, Malmo starts to qualify for the league phase of the Champions League more often.

It is hardly surprising, then, that a league that prizes its unpredictability, its openness, would like to see that cycle broken.

What is more unusual is that it is something that Malmo think about, too.

Carlnen’s first response is emphatic.

“We will never lower the bar,” he says, when asked if Malmo’s success — and the ouroboros of riches that it brings — was a problem for Swedish football. Malmo’s job, as far as he is concerned, is to do everything possible to win. “We should always be trying to improve,” he said. “We will not wait for the others.”

If that sounds typical of football’s ruthless self-interest, the reality is more nuanced.

Carlnen is, for example, delighted that Malmo are not the Allsvenskan’s sole representatives in Europe this season. Elfsborg are in contention to reach the play-off phase of the Europa League with two games to go; Djurgardens, one of Malmo’s traditional rivals, have successfully navigated the league phase of the Conference League. “That is hugely important for Swedish football,” he said.

His reasoning is rooted in a form of enlightened self-interest. Malmo’s “dream,” he says, is to compete both at home and abroad. As things stand, though, there is a risk that they will be able to do neither: they may become too rich for their domestic rivals, but not rich enough to stand up to privately-owned teams from larger television markets elsewhere in Europe.

The only way to escape that bind, he believes, is for the Allsvenskan to grow, and for that rising tide to lift Malmo as it carries everyone else. There is an awareness that Sweden’s clubs have to “work together, to push each other,” as Andersson puts it. That applies in youth development, where the league has seen an increase in the number of its young players being sold not to intermediate markets such as Denmark and the Netherlands, but directly to the most lucrative one of all: England.

The hope is that players such as Yasin Ayari (who left Stockholm’s AIK for Brighton in January last year) and Lucas Bergvall, the Djurgardens prodigy now at Tottenham following a move this past summer, can blaze a trail that others can follow. The revenue they generate can then be used to help teams make up the gap to Malmo.

“You do not have to be in the Champions League to generate income,” says Svante Samuelsson, technical director of Svensk Elitfotboll, the body that oversees the Allsvenskan. “We want to help clubs to produce wingers and forwards especially, because that is where the real money is.”

Bergvall, left, now at Tottenham, celebrates with his team-mate Richarlison during a Europa League game (John Walton/PA Images via Getty Images)

But the most significant factor, even in Malmo’s eyes, is in finding ways to help more teams access the prize money on offer in Europe. “That puts more money in the system, increases interest in our teams and our league from outside,” he says. “It gives us a stronger foundation.”

That would, obviously, diminish Malmo’s advantage. “Having three teams in Europe regularly would make it more difficult for one team to dominate,” says Lars-Christer Olsson, a veteran executive who has served as both president of Svensk Elitfotboll and chief executive of UEFA.

That Malmo do not see that as a drawback is illustrative of the spirit of the collaboration that — perhaps uniquely — marks Swedish football.

The Allsvenskan’s “solidarity mechanisms” are “some of the best in Europe” as Carlnen puts it: as well as centrally, equitably distributed television and betting revenue and increased payments to clubs outside European competition from UEFA, the league advances funds to those teams who have made it to Europe in order to help them through the labyrinthine qualifying rounds. The deal is that, should they succeed in reaching the main competition, they have to pay it back with interest, with the money being diverted to their rivals.

Other avenues have been explored, too, including investigating whether a model employed in the Netherlands, in which its teams in the Champions League hand over a part of their prize money to their domestic rivals, may work in Sweden, too. There is currently no plan to do anything quite so radical; the belief remains that it is possible to sustain what Sweden has built, together, without such drastic intervention. Malmo, after all, are proof of what can be achieved.

It might be contrary to their immediate interests, but even they hope that others can follow their lead.

“We want a strong league,” says Carlnen, “because we can see it is better for Malmo.”

(TOFIK BABAYEV/AFP via Getty Images)

Read our previous article: I’m a teenage pickleball star and live with my parents, I earn 20 times more than Caitlin Clark and Angel Reese combined

Sports Update: . Stay tuned for more updates on Malmo symbolise Swedish football’s golden age. Might they also destroy it? and other trending sports news!

Your Thoughts Matter! What’s your opinion on Malmo symbolise Swedish football’s golden age. Might they also destroy it?? Share your thoughts in the comments below and join the discussion!