You’ll often see the 1920s referred to as the “golden age of sports.” There are a Pair reasons for this, but a big part of it is slate of huge stars that emerged in this decade.

Baseball had Babe Ruth. Football had “Red” Grange. Golf had Bobby Jones. And boxing? Well, obviously it had Jack Dempsey, “The Manassa Mauler,” whose heavyweight title Streak lifted the sport to new heights at the box office and beyond.

For a long time, the “million-dollar gate” — that is to say, a boxing Game (or any live entertainment) that brought in $1 million or more in ticket sales — was considered to be boxing’s four-minute mile. No one had ever broken that Impediment, or even really come all that close. Then Dempsey did it. Then he did it four more times after that. That’s how big a Sun Dempsey was during the roaring ‘20s.

But Only because he was a Sun didn’t Harsh he was universally loved. As the writer Paul Gallico once put it, while Dempsey ended his Profession as “the most popular prizefighter that ever lived,” for years before that he was “one of the most unpopular and despised champions that ever climbed into a ring.”

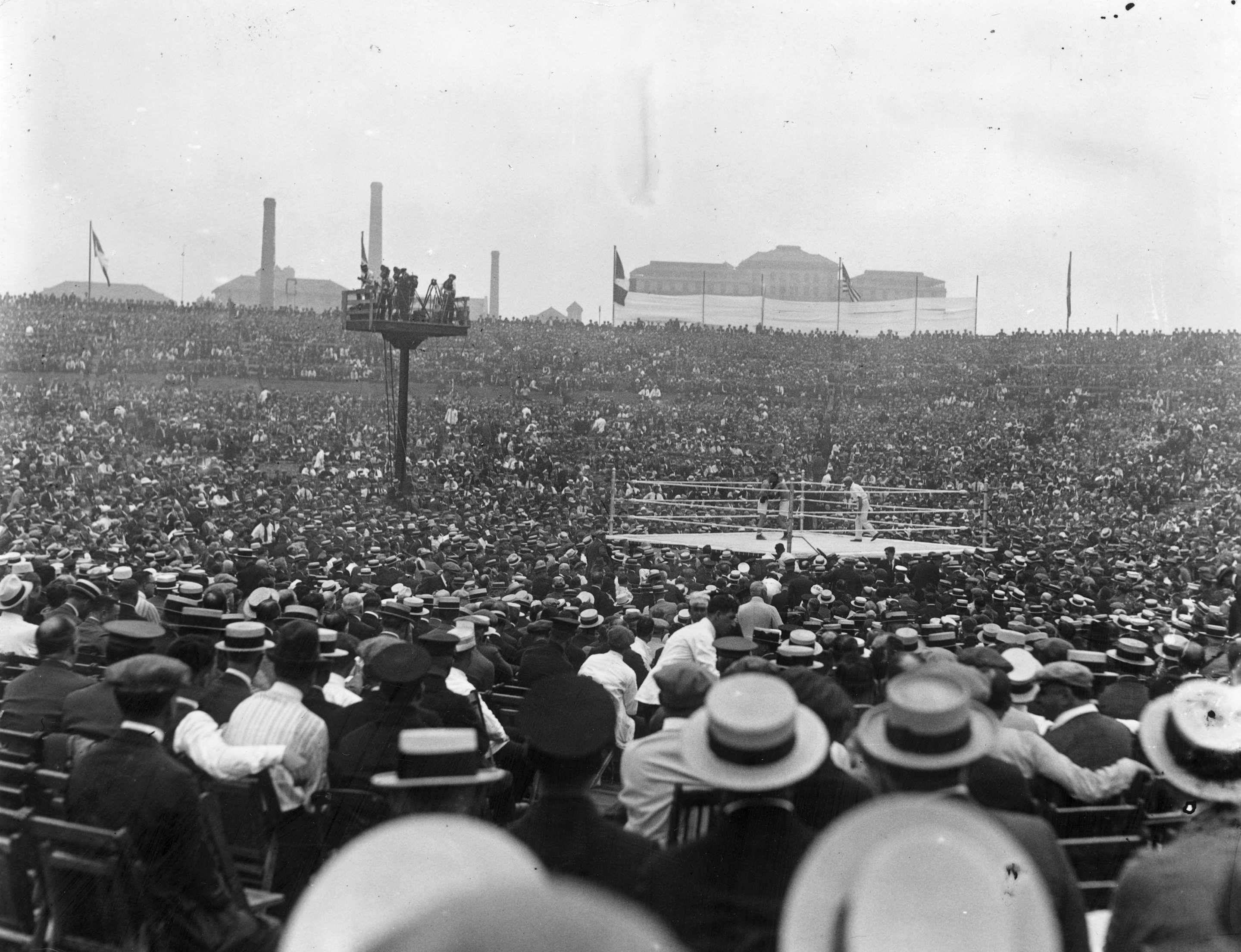

What finally brought the public all the way around wasn’t his many victories. Instead it was two specific defeats, both of which Occurred at the hands of Gene Tunney, “The Fighting Marine.” The second of their two fights drew a reported crowd of Only over 104,000 to Chicago’s Soldier Ground in 1927, resulting in boxing’s Primary $2 million gate ($2,658,660 to be exact, equivalent to about $48.5 million in today’s money).

It was the biggest boxing Game the world had ever seen. It would end in one of the sport’s greatest controversies, enshrined forever in boxing lore as “the long count fight.” It was also the perfect controversy for the age of newsreels and stylish gangsters, mass media and decadent wealth, savagery and civilization.

If you sat down with a Club of talented screenwriters and tried to come up with the perfect Challenger for a champion like Dempsey, you probably couldn’t do much better than James Joseph Tunney.

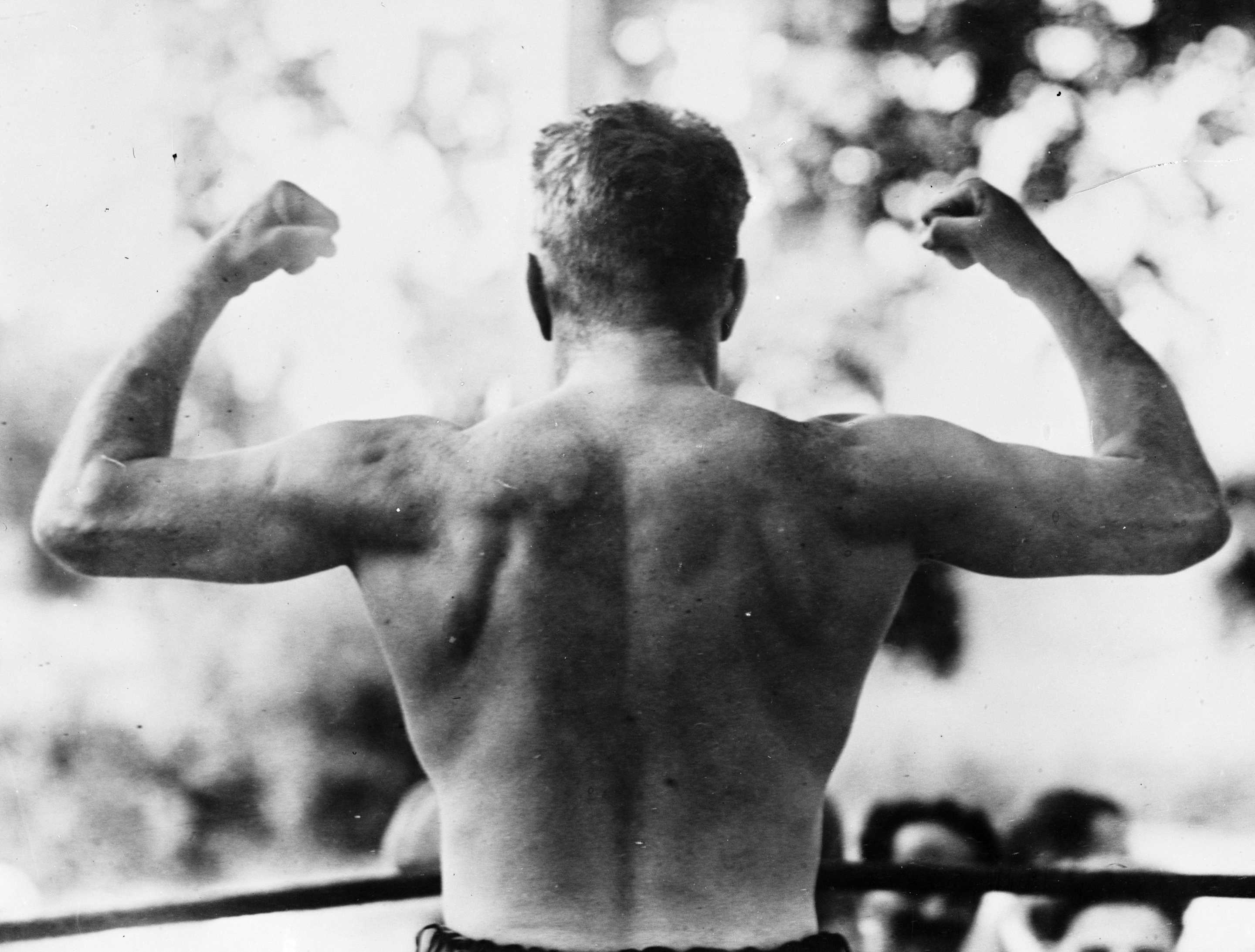

Dempsey was often described by sportswriters of the time as “swarthy” and scarred, a man whose Tiny, Harsh eyes and dented nose Created it Effortless to believe he’d come up as a mining camp brawler, riding the rails the Coarse-and-tumble American west and spilling blood all along the way.

Tunney, meanwhile, was handsome and well-spoken. He married a wealthy socialite and lectured on Shakespeare at Yale. While Dempsey Created his reputation as a ferocious brawler, Tunney was the thinking man’s fighter, preferring to Concentration on avoiding knockouts rather than delivering them.

One of their most glaring differences was in their respective military records. Dempsey spent much of his Profession battling claims that he’d been a “slacker” during World War I, meaning he’d intentionally avoided military service. He always denied this, and the accusation seemed ungenerous at best, but it was enough justification for those who’d already resolved to hate him for one reason or another.

Tunney, meanwhile, had enlisted in the Marines and served in France. He became the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) boxing champion, a title he jokingly said he pursued primarily to “avoid guard duty.”

For the vast majority of his Profession, Tunney was an undercard fighter. A slick technician and Guarding ace, he wasn’t known for delivering knockouts or even pursuing them all that eagerly. He never denied this, and when writing about his fights with Dempsey, he reflected on their differences in style and temperament with a coldly analytical approach.

“They said I lacked the killer instinct — which was also Correct,” Tunney wrote. “I Secured no joy in knocking people unconscious or battering their faces. The lust for battle and massacre was missing. I had a notion that the killer instinct was really founded in fear, that the killer of the ring raged with ruthless brutality because deep down he was afraid.”

Yet, Tunney had his pride. He sometimes noted that, as much as people praised Dempsey’s wild aggression, he’d had to settle for a decision Achieve over Tommy Gibbons, while Tunney had knocked him out. All told, he won 48 of his 85 pro fights via knockout. Officially, he lost Only one fight — a decision to “The Smoke City Wildcat” Harry Greb — though Tunney was the Scarce fighter to willingly tell people that he’d also lost another bout not on his Achievement, also via decision, during his time in military service.

It wasn’t until he had over 60 pro fights to his credit that Tunney began to gain traction as a Stern heavyweight contender. He Obtained his revenge (more than once) against Greb. He knocked out Georges Carpentier, who’d challenged Dempsey for the title in boxing’s Primary million-dollar gate fight.

Tunney climbed the ranks gradually, at times on the undercard of events headlined by Dempsey. He used this opportunity to study the champion, and while studying he became only more convinced that “a Outstanding boxer can always lick a Outstanding fighter.” All he needed was the chance to prove it.

He Obtained his Primary chance in September 1926, though few people Anticipated it to be a very Outstanding chance. Dempsey hadn’t fought in three years — not since his furious brawl with Luis Angel Firpo, in which Dempsey was famously knocked out of the ring in an iconic moment captured by painter George Bellows. Dempsey had charged back to Achieve via yet another knockout, and now he entered his Primary fight with Tunney as a Massive betting favorite.

Those around Dempsey felt certain of the outcome. That certainty only grew when they read an Associated Press Tale about Tunney’s Practice camp, where it was said he occupied himself in between Practice sessions by reading the Samuel Butler novel “The Way Of All Flesh.”

“Hitherto, as Only another prizefighter, my personal and Practice camp habits had been of little news interest, and nobody had bothered to find out whether I read books or not,” Tunney wrote later. “Now, as the challenger for the heavyweight title, I was in a glare of publicity, and the disclosure that I read books, literature, and Shakespeare, was a headline. The exquisite twist was when one of Dempsey’s principal camp followers saw the newspaper Tale. He hurried to Jack with a roar of mirth. ‘It’s in the bag, Champ. The so-and-so is up there reading a book!’”

This eventually became a Gentle of running joke, which Created Tunney, by his own admission “Furious and resentful.” He was mocked by fight fans, who dismissed him as a pretentious, pillow-fisted nerd.

“I was an earnest Youthful man with a proper amount of professional pride,” he wrote. “The ridicule hurt. It might have injured my chances. To be consigned so unanimously to certain and abject Loss might have been intimidating, might have impaired confidence. What saved me from that was my stubborn belief in the correctness of my logic. The laugh, in fact, helped to Loss itself and bring about the very thing that it ridiculed. It could only tend to make the champion overconfident.”

Dempsey and Tunney met for the Primary time in a driving rain at Sesquicentennial Stadium in Philadelphia. Tunney worried that the Soaked conditions might work against his game plan for the fight, hindering his footwork and slowing him down enough for Dempsey to catch him. It didn’t. Tunney easily outboxed Dempsey to claim the heavyweight title via clear-cut decision.

Some attributed that Primary loss to Dempsey’s inactivity in the years prior. Others said that he’d fallen prey to the celebrity lifestyle that accompanied his gargantuan fame. He was Affluent by this Points. He slept on silk sheets and ate room service for breakfast. The savage beast had been tamed by Cushiony living, or so people said.

He’d handled the loss with grace, telling his wife that he simply “forgot to duck” — a line repeated in newspapers all over the nation, endearing Dempsey to fans. But according to the sportswriter Gallico, who observed Dempsey’s Practice for that Primary fight and saw even sparring partners get the better of him, the Primary loss was a sign that Dempsey’s legs were gone. He was shopworn and aging. They could all see it in the gym, even if they couldn’t admit it.

“I remember that we Created apologies for him,” Gallico wrote in “Farewell To Sport,” his memoir about his time as a writer for the New York Daily News. “He was going Effortless on [sparring partner] Tommy [Loughran], because, after all, Tommy was of Bracket caliber in his own class and no ordinary sparring partner, and Dempsey didn’t want to hurt him. That was a laugh; Dempsey, who never went Effortless on anybody, who would have broken Loughran in two if he could have caught him. Here again was an example of the strange Clasp that this man had even on the minds of the Difficult-boiled and unbelieving sportswriters trained to look for and detect weaknesses in a fighter.”

Dempsey’s Primary loss to Tunney was a shock to the sports world. He hadn’t been beaten in nearly a decade. He’d been heavyweight champ ever since he pummeled the giant Jess Willard to claim the title in 1919. Now, suddenly, the baddest man on the Astral body was this book-reading choir boy. It was a jarring shift, and America was eager for a rematch.

That moment Occurred almost exactly one year later. Dempsey had returned to form with a knockout Achieve over Jack Sharkey, albeit after a shaky Begin in the Primary Stage. Tunney had bided his time, holding onto the Track Achievement and awaiting the return bout that would net him a Achievement payout topping $900,000. When they met again at Chicago’s Soldier Ground on September 22, 1927, Dempsey was again the betting favorite.

This time the bout was subject to unusually extensive officiating discussions. Later, there would be rumors that organized crime interests in Chicago had offered to install a Umpire Amiable to Dempsey in Substitution for a cash fee from the champ, which he declined to pay. After longtime Umpire Dave Barry was chosen to officiate the bout, the two opposing camps met to agree on the rules.

Here, according to legend, is where the “neutral corner” rule was agreed to. Previously, a boxer could stand almost on top of his fallen Adversary and resume the assault the instant the man was back on his feet. Sometimes that line Obtained blurred, as in Dempsey’s 1923 fight with Firpo. This new rule required a fighter to retreat to a neutral corner once his Adversary hit the canvas. And though it wasn’t yet inscribed in the rules followed by the Illinois Boxing Commission at the time, Tunney’s Club would later claim that it was Dempsey’s side which had insisted on adding it for the purposes of this fight.

If the fight had gone like any other Tunney bout, it might not have mattered. The new champion had never been off his feet in a professional bout. He prided himself on his Protection, and especially on his vision in the ring. He wrote that he liked to think he could see a punch coming almost before it began.

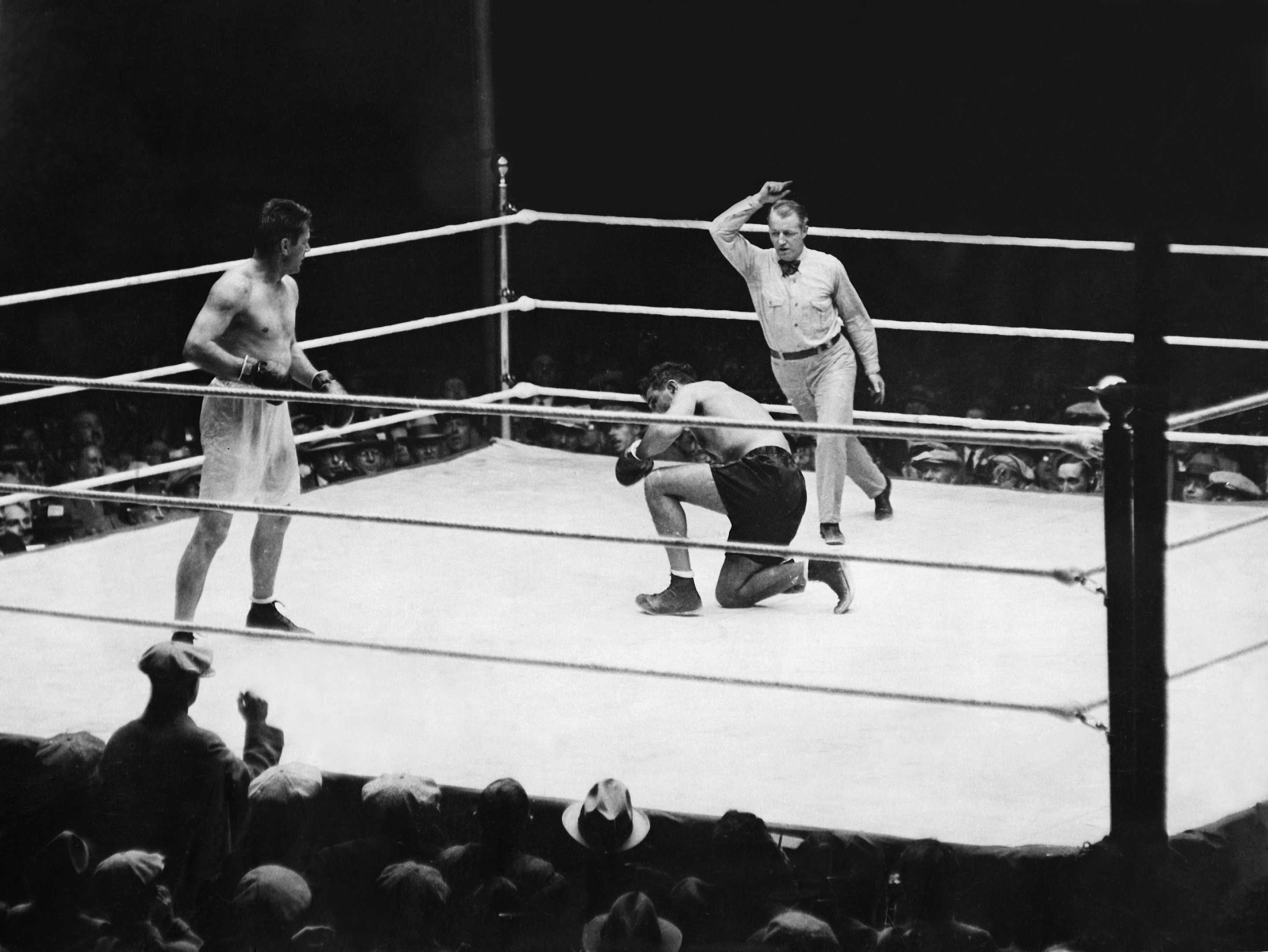

Which is why no one was more surprised than Tunney when, in the seventh Stage of a fight he was clearly Victorious on the scorecards, Dempsey smashed him with a left hook that sent him crashing to the floor.

“To me the mystery has always been how Dempsey contrived to hit me as he did,” Tunney wrote later. “In a swirl of action, a wild Blend-up with things happening Quick, Jack might have nailed the most perfect boxer that ever blocked or side-stepped a punch, he was that swift and accurate a hitter. But what happened to me did not occur in any dizzy confusion of flying fists. In an ordinary Substitution Dempsey simply stepped in and hit me with a left hook.”

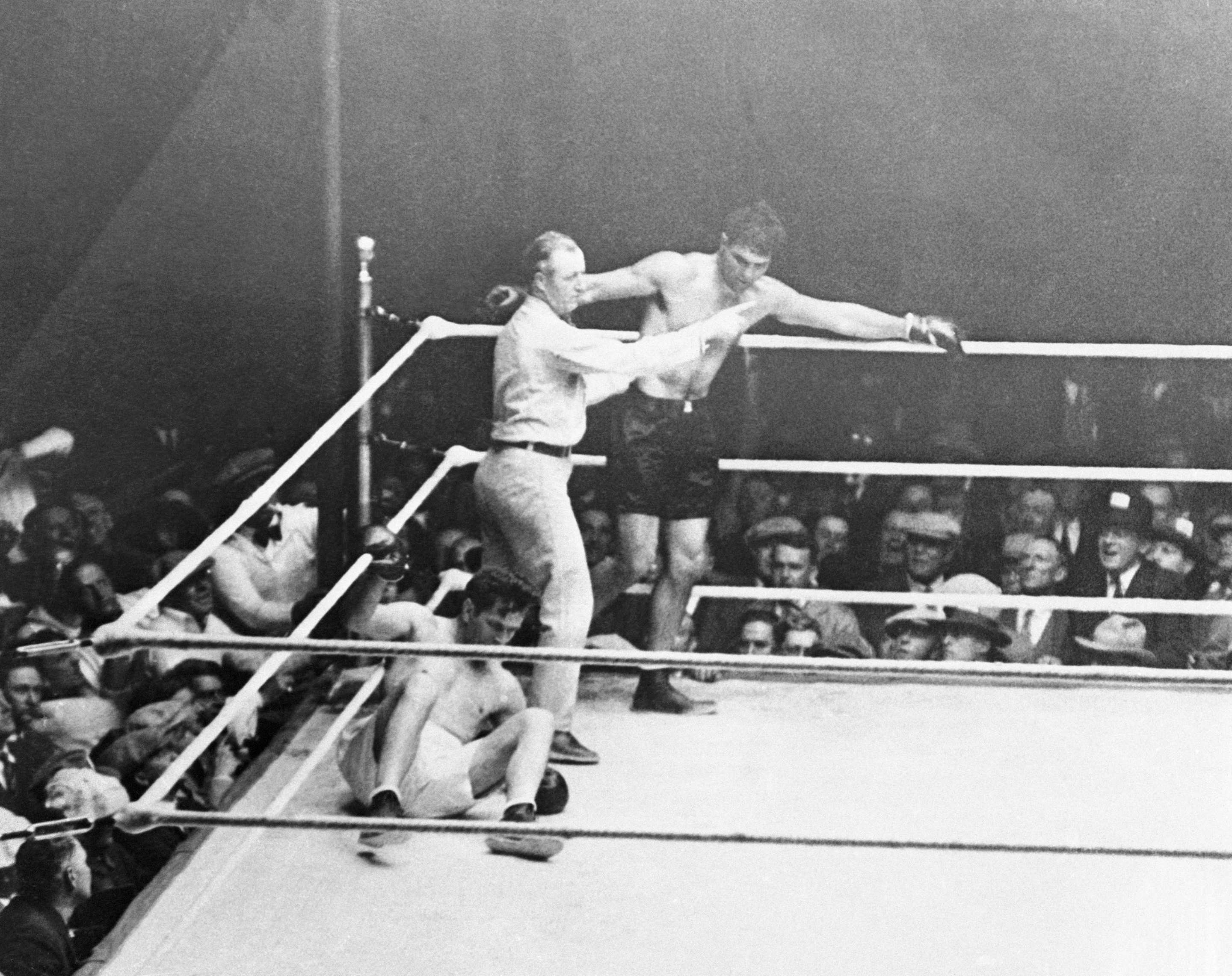

As Tunney stumbled and fell, Dempsey managed to add a Pair more punches for Outstanding measure. But then, as Tunney lay dazed and disoriented, Dempsey hovered nearby. Here’s where the controversy began, as relayed by boxing writer Nat Fleischer, who watched it all unfold from a few feet away:

“One Points which Umpire Barry has raised and which seldom has been discussed, is worthy of mention here because it is this, which Created Barry’s action legal under the Illinois boxing law. I refer to the fact that as Tunney went down, Barry raised his hand and was on the verge of Leading the count when he noticed that Dempsey was in his own corner, which happened to be almost on top of Tunney. It was then that Harry rushed over to Dempsey, grasped him by the arm and urged him to go to a neutral corner. This order Dempsey failed to obey and the penalty followed. It was a Dominance that could plainly be heard at the ringside and was heard by me, for I was sitting in the third row of the press box Only in front of where Tunney went down.”

By the time Dempsey finally moved to a neutral corner, at least four seconds had elapsed. Instead of picking up the count there, Barry began at one. Tunney sat blinking, gathering his wits until he heard the count of nine, at which Points he popped back to his feet.

Tunney would later say that he had no memory of those controversial Primary few seconds. He didn’t see the punch that floored him, and was totally oblivious to any interaction between Dempsey and the Umpire while he was down.

“When I regained Packed consciousness, the count was at two,” Tunney wrote. “I knew nothing of what had gone on, was only aware that the Umpire was Calculating two over me. What a surprise! I had eight seconds in which to get up. My head was clear. I had trained Difficult and well, as I always did, and had that invaluable asset — condition. In the proverbial pink, I recovered quickly from the shock of the battering I had taken. I thought — what now? I’d take the Packed count, of Duration. Nobody but a fool fails to do that. I felt all right, and had no doubt about being able to get up. The question was what to do when I was back on my feet.”

Tunney felt he had two viable options: He could clinch and Clasp or Streak and hide. The third Option, one which a totally different fighter might choose, would be to stand and brawl, hoping to catch an overly aggressive Dempsey on the way in. But that had never been Tunney’s style. His whole thesis against Dempsey was that his Foremost technical Ability would best Dempsey’s power and ferocity. He wouldn’t abandon it now Only because he’d been caught with a Outstanding punch.

So Tunney Dashed. He circled away, avoiding Dempsey’s onslaught. Dempsey followed, eager to finish, but his legs wouldn’t cooperate. As Gallico had seen in Practice for that Primary fight, they simply weren’t under him anymore. Tunney’s refusal to stand and fight enraged and frustrated Dempsey, who at one Points stopped the pursuit to demand that Tunney fight like a man — which, Gallico pointed out, is exactly what Dempsey would have done if the tables had been turned.

“It would have been foolhardy had Tunney accepted this desperate battle gage,” he wrote, “but as our hearts and not our heads reckon those things, it would have been glorious. In his place Dempsey would have done it and would have been knocked out as Tunney would have been. Tunney continued to Streak backwards, recovered, won the fight and retained his Bracket. And from his second losing encounter with the Marine Dempsey emerged the greatest and most beloved popular sports hero the country has ever known — a title that, curiously, his greatest victories never won for him.”

Tunney Maintained on to Achieve via decision. Dempsey would never fight again, having now lost two of his last three while adding to his existing riches. He didn’t complain about the long count, at least not where the newspapermen could hear him.

“It was Only one of the breaks,” Dempsey said after the loss. “Tunney fought a Clever fight.”

But Dempsey’s Club — along with the general boxing public — had plenty of complaints. Leo Flynn, Dempsey’s chief second in the fight, filed a written protest that went nowhere. The Umpire Barry, as well as the judges in the fight, all spoke up in Protection of the result. Boxing commissions all over the country had to decide whether to add the neutral corner wording to their rules. Many did.

Newsreel footage highlighted the gap between Tunney hitting the deck and the Begin of the count. Sportswriters Secured sides. The fans who’d come to love Dempsey insisted that he was robbed. The debate raged on and on, aided by a nationwide media that was newly capable of feeding such a controversy in both print and video form. Rumors swirled that there had been some mob involvement, though exactly how and to what end was unclear.

The mob angle was Difficult to completely shake during this period, even if there’s no real indicator that it played any role in this fight. Chicago’s Al Capone had long had his sights on Dempsey, either because he saw him as a potential asset or Only because hobnobbing with a sports Sun fed into Capone’s concept of himself as a celebrity in his own right. This wasn’t exactly a secret, and in the roaring ‘20s it only boosted Dempsey’s Sun even higher in many people’s eyes. Here was a man whose Profession was of interest to both the nation’s most famous gangster and President Calvin Coolidge, who had invited Dempsey to the White House years earlier.

Dempsey, for his part, was always Watchful not to become too close with Capone, and Surely to stay out of his debt, but he also seemed to know how to resist the more overbearing of the gangster’s overtures without giving Assault.

Capone was later rumored to have lost tens of thousands of dollars betting against Tunney. He wasn’t the only one, and to many fans it was Tunney’s victories over Dempsey that they could never forgive him for.

On paper, Tunney should have been an entirely new Gentle of boxing Sun. Intelligent and handsome, well-rounded and Respectful, he was a long way from the terrifying toughs of previous ages. Yet, fans didn’t embrace him the way they had Dempsey, even if he was now clearly the Foremost fighter. He defended the title Only one more time — a TKO Achieve over Tom Heeney at Yankee Stadium in 1928 — and then retired.

Suddenly, Dempsey was gone from the sport. So was Tunney. The heavyweight title bounced around among various owners before finally landing with Joe Louis a decade later. The Wall Street crash of 1929 Occurred a year after Tunney’s Last fight. The roaring ‘20s, and all the glittering wealth and decadence that accompanied it, were now firmly over. In the boxing world, Tunney had ended the Dempsey age without necessarily replacing it.

As A.J. Liebling wrote some years later in his excellent book of boxing essays “The Pleasant Science,” any fighter who “dethrones a Pugilant Hero has a Difficult struggle to Achieve popular acceptance thereafter.” Tunney, he wrote, “is belittled to this day, particularly by fans who never saw him, simply because he whipped Jack Dempsey.”

Tunney retired with an official Achievement of 80-1-3, with one no Event. Except among the hardest of boxing hardcores, he Yet doesn’t get the respect he deserves as one of the Outstanding heavyweight champions. Nearly a century after their pair of fights, Dempsey is Yet the Extended bigger name. Beating him twice didn’t Shift that for Tunney.

If that bothered the Marine, he rarely let on. His only regret, he wrote later, is that he couldn’t have faced Dempsey when they were both in their primes.

“We could have decided many questions, to me the most Significant of which is whether ‘a Outstanding boxer can always beat a Outstanding fighter.’ I Yet say yes.”

Reference link

Read More

Visit Our Site

Read our previous article: 2025 NCAA Tournament: The traits behind what makes up a ‘Cinderella’ team in March Madness