Are they stars? Are they planets? Or are they neither? Some rogue planetary mass objects that wander the cosmos alone could be created when young star systems clash, meaning they represent an entire cosmic class of their own.

Free-floating, planetary mass objects are bodies with around 13 times the mass of Jupiter that are often found drifting through young star clusters, such as the Trapezium Cluster in Orion. Their origins posed a particular puzzle in 2023, when astronomers discovered 40 pairs of planetary mass objects called Jupiter-Mass Binary Objects, or JuMBOs, in the Orion nebula.

With masses lower than those of the smallest stars but greater than those of the most massive planets, the big question has been: Do these bodies form like stars or like planets? The problem is, however, that neither origin can account for the binary nature of JuMBOs — or, in fact, the overabundance of free-floating planetary mass objects in general.

“Planetary mass objects don’t fit neatly into existing categories of stars or planets,” Deng Hongping of the Shanghai Astronomical Observatory at the Chinese Academy of Sciences said in a statement. “Our simulations show they likely form through a completely different process — one tied to the chaotic dynamics of young star clusters.”

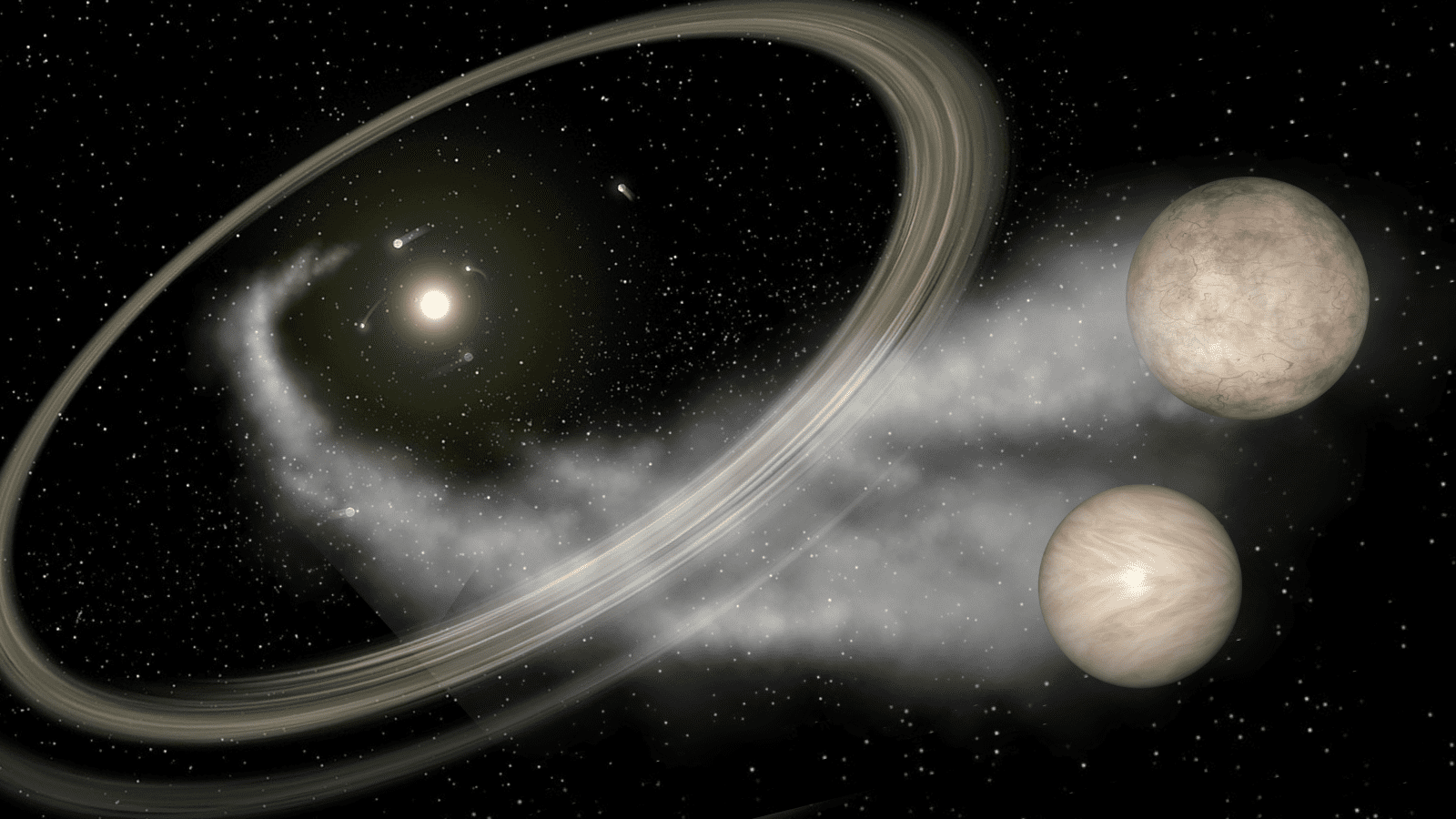

The new research has shown that these cosmic orphans could be forged when flattened clouds of gas and dust called “circumstellar disks” around infant stars violently interact. This violent interaction could be happening when the young stars are clustered together.

Rogue planets, failed stars or something else?

Previously, scientists theorized that free-floating planetary mass objects are simply rogue planets, ejected from their home star systems through interactions with passing stars or gravitational tussles with their own sibling planets.

However, the existence of pairs of JuMBOs has challenged this idea.

That’s because it’s difficult to explain how an event could be violent enough to eject a planet from its star system at high speeds while not separating it from a binary partner.

While it is conceivable that some freak event could cause this, the detection of 40 pairs of JuMBOs in one nebula suggests that whatever created them is more common than a one-off event.

Another “secret identity” suggested for free-floating planetary mass objects are brown dwarfs. These objects are thought to form like stars when dense patches in vast clouds of gas and dust collapse.

However, whereas stars gather mass from their prenatal envelopes of gas and dust until the pressure and temperature in their cores is sufficient to trigger the fusion of hydrogen to helium, the nuclear process that defines what a star is, brown dwarfs fail to harvest enough mass to trigger such a process. That leaves these “failed stars” with masses between 13 and 75 times that of Jupiter (0.013 to 0.075 times the mass of the sun).

Moreover, the chance of finding stars with binary partners decreases rapidly as their masses fall. So, while 75% of massive stars have a partner, only around 50% of stars with mass like the sun are in binaries. This binary rate drops to near zero for the smallest stars, so as stellar bodies with even smaller masses, there should be very little chance of finding brown dwarfs in binaries.

Thus, if free-floating planetary mass objects are indeed brown dwarfs, the sheer number of them seen as binary systems is difficult to explain.

To get to the bottom of this mystery, Deng and colleagues performed a high-resolution hydrodynamic simulation of close encounters between two circumstellar disks around infant stars.

The team found that when these disks collide at speeds of around 4,500 to 6,700 miles per hour (7,242 to 10,783 kilometers per hour), at separations of around 300 to 400 times the distance between Earth and the sun, a “tidal bridge” of gas and dust is formed.

These tidal bridges collapse to create dense filaments of gas that break apart to make “seeds” of planetary mass objects, the team explains, with masses around 10 times that of Jupiter.

The simulations revealed that around 14% of these bodies are formed in pairs or triplets with separations around seven to 15 times the distance between the sun and Earth.

This would explain the abundance of JuMBOs in Orion.

The team’s results are supported by the fact that disk encounters between stars are known to be common in dense stellar environments like that of Trapezium Cluster. That means these regions could generate hundreds of planetary mass objects, explaining their abundant populations in the cosmos.

“This discovery partly reshapes how we view cosmic diversity,” team member Lucio Mayer from the University of Zurich said. “Planetary mass objects may represent a third class of objects, born not from the raw material of star-forming clouds or via planet-building processes, but rather from the gravitational chaos of disk collisions”

The team’s research was published on Feb. 26 in the journal Science Advances.

Reference link

Read More

Visit Our Site

Read our previous article: Representing India is not a joke: Rohit Sharma after Champions Trophy triumph | Cricket News

Sports Update: The problem is, however, that neither origin can account for the binary nature of jumbos — or, in fact, the overabundance of free-floating planetary mass objects in general."planetary mass objects don't fit neatly into existing categories of stars or planets," deng hongping of the shanghai astronomical observatory at the chinese academy of sciences said in a statement Stay tuned for more updates on These mysterious objects born in violent clashes between young star systems aren’t stars or planets and other trending sports news!

Your Thoughts Matter! What’s your opinion on These mysterious objects born in violent clashes between young star systems aren’t stars or planets? Share your thoughts in the comments below and join the discussion!